Art, Meet Architecture

Works of Frank Gehry and Richard Serra in conversation

Art, Meet Architecture

As disciplines, art and architecture can be fast friends or distant cousins, but in rare cases they can be soul mates. This happens to be true with Frank Gehry’s design for the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, which opened in 1997. In February of 2017, I was fortunate to spend a couple days touring the collections, exhibitions and the building itself – a work of sculpture in its own right. To call it sculpture though, is not enough. While its grand, sweeping gestural forms, torqued geometries and seeming self-referential identity of the building confirm the building’s iconic status (art historian Hal Foster critiques it as “primarily in service to corporate branding,”) Gehry’s design brilliantly marries the building’s architecture to the art it contains. This is most evident in the long exhibition hall designed specifically to showcase Richard Serra’s monumental work, The Matter of Time.

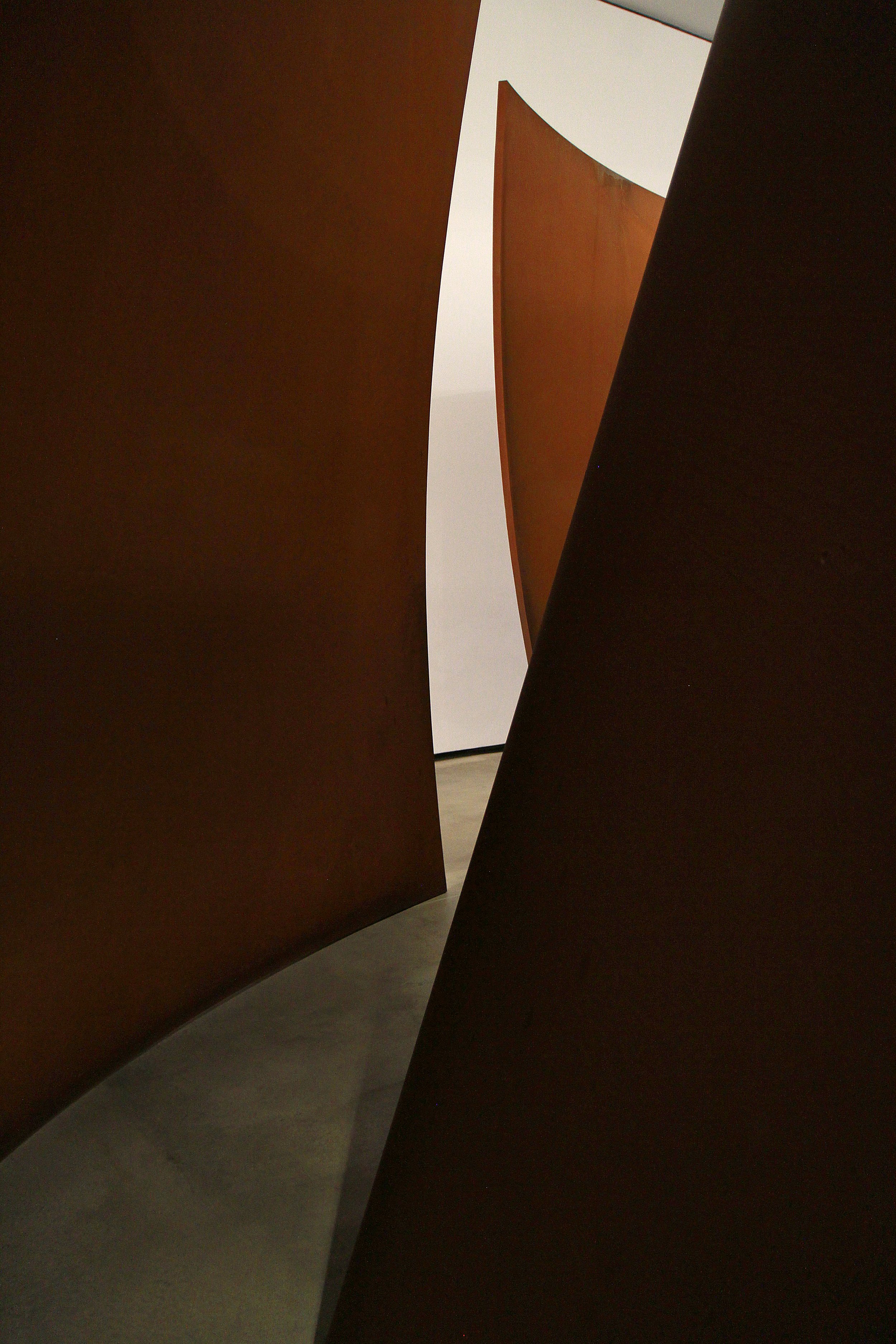

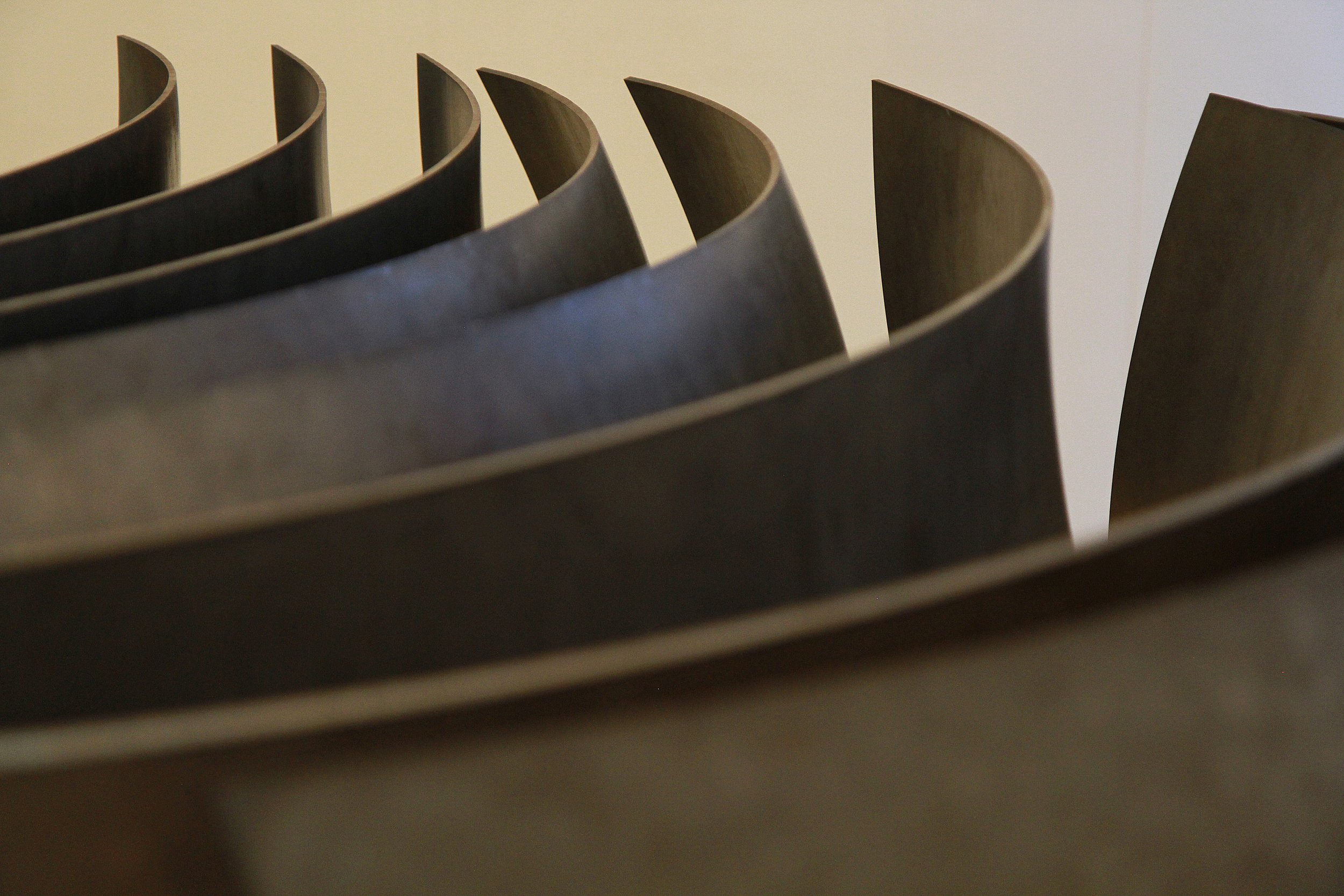

Serra’s monumental work is massive. Weighing in at 1,034 tons, it fills the main gallery, which is 430 feet long by 80 feet wide. It is eight sculptures in one, each comprising multiple sheets of two-inch thick rolled steel that form 14-foot high curling walls and twisting pathways. Serra invites visitors to engage the work at both monumental and human scales. Walking between or alongside these towering metal walls, one becomes aware of the disorienting effect of sloping surfaces pushing left then right as spirals reverse upon themselves then open on cavernous rooms. The chemically-treated metal surface presents varied patinas of light and dark rust, sometimes appearing in rivulets or creeping stains that evoke the passage of eons. Passing along these surfaces, the sounds of footsteps bounce against the panels and the echo shifts pitch and delays as the journey progresses. Looking up or through a sudden opening, glimpses of the gallery’s architecture appear and the relationship between Serra’s work and the building becomes evident. When inside the sculpture’s many walls, openings frame positive and negative space that mimic the building’s exterior forms.

It's evident that Gehry made multiple nods to the Guggenheim Museum in New York designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, including organizing the galleries and exhibition spaces around a central glass atrium, which overlooks the Nervión River. A series of catwalks and stairways serve the same function as Wright’s continuous spiral path. The use of curving plaster walls which interrupt the exposed structural steel is another. Skylights allow daylight to wash down the smooth plaster walls. In this way, both architects are using light as a material.

Gehry explored similar architecture ideas at two other cultural institutions: The Weisman Art Museum and the Walt Disney Concert Hall. The Weisman (1993), located at the University of Minnesota, is arguably Gehry’s first experimentation with the sculptural ideas expressed in the building’s façade, although the interior spaces are rather conventional when compared to the Guggenheim’s. Los Angeles’ Disney Concert Hall (2003) provides the grand finale in the design trio. While the engineering for the Weisman was calculated manually, computer software was utilized to engineer the structures and complex forms of the Guggenheim and Disney Hall. In the case of the Weisman, one could say that the sculptural façade is simply applied to a box with a more traditional arrangement of gallery spaces. Disney Concert Hall’s interior architecture likewise conforms to a conventional program to accommodate the acoustic, circulatory and occupancy requirements of an auditorium. Despite these constraints, Gehry managed to sculpt metal panels into graceful, undulating forms that animate the exteriors of all three structures. A sense of movement is amplified by the play of light on the reflective surfaces which seem to change color and intensity with the movement of the sun, change in weather, or position of the observer.

During an interview on the Weisman design, Gehry said that he was not interested in designing a building that would blend into the existing University of Minnesota campus vernacular. He accomplished this in spades. His design for Disney Hall met all its functional requirements as well, while at the same time allowed him to further develop his own iconic ideas. Undoubtedly, his finest achievement is the Bilbao Guggenheim, where the architecture dramatically enhances the art it contains. Each would be diminished without the other.

— Tim Heitman